Format War: Every Format for Itself

September 27th, 2021 | by Andreas Richter

(12 min read)

This is a feature that is touching different topics that we all somehow meet in our usage of mobility. Starting at re-inventing the wheel of describing the traffic environment, e.g. for automated driving, we have to talk about the battlefield where this war takes place… and about the most important participant who currently seems not to know that he is the most important one. Thus, we will talk about:

- Different road description formats in the automotive industry describing the same road,

- the IT industry working on automated driving with the need of describing the world,

- and the public authorities operating and maintaining the roads in this world.

But first, let’s start with the basic to subdue the world: describing it.

When IT systems came up, also the need of a systematic way of organizing the data in proper formats had to be addressed. Different stakeholders developed different solutions: Public authorities and road operators used computer aided design (CAD) to digitalize the paper plans they had. Automotive industry used simulations to improve the development process as well as to test and evaluate new systems and the customer experience. Mobility providers and all the fancy data-driven marketplaces had not appeared on the horizon, yet.

First Force: Automotive Industry

In automotive domain the navigation use case was the first driver of dealing with (geo-)data for customer services. A lot of proprietary formats were developed and the wish of the OEM came up not to become subject to vendor lock-in. The Geographic Data Files (GDF) format was developed and standardized as interchange format to describe large road networks as nodes and edges enriched with attributes and relations. Most map vendors are providing their data in GDF format.

Nevertheless, also the usage of the huge amount of data was challenging and therefore automotive industry again tried to standardize not only the format but also the architecture to meet automotive-grade quality of the data. The Navigation Data Standard (NDS) was such kind of solution and, again, most of the map vendors are able to deliver their data in NDS as well.

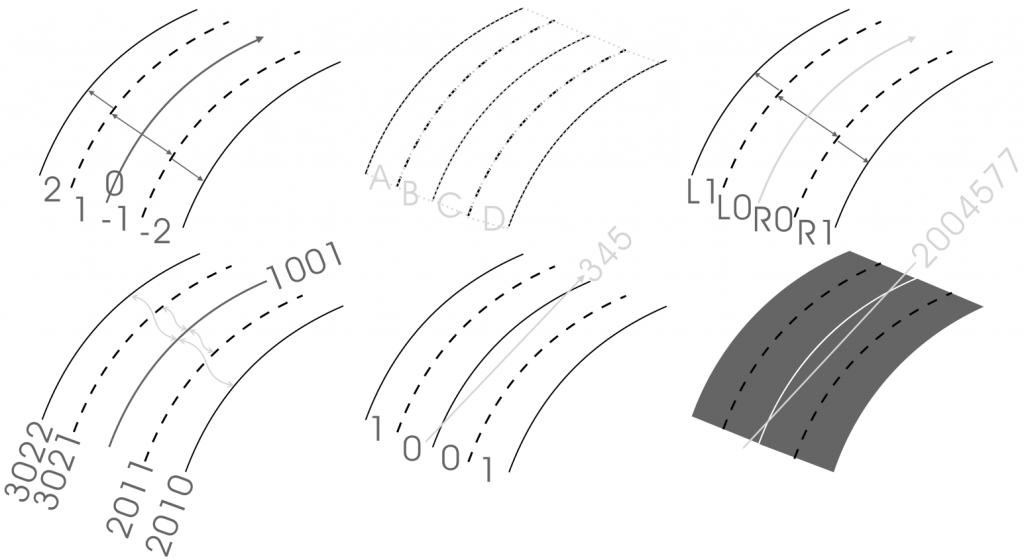

In the meantime, more and more driver assistant systems were introduced that, in early development stages, were tested in simulation. Therefore, the simulation had to describe the environment and the road as well in a detailed level. A lot of tools were developed and they tackled the challenge of defining the road their own way. Every tool provider thought that his own format was the best choice and, again, imposed a vendor lock-in on the customer. Some companies saw that the format will not be the most important competitive advantage but more the interface to other tools and, therefore, also the need of interchanging data. The format OpenDRIVE is the most prominent example, first developed by industry companies, OEMs and research institutes and made public royalty-free. Other formats such as RoadXML went the same way but OpenDRIVE is already widely used because it was open from an early stage. Starting as a simulation format with focus on manual road creation using an editor OpenDRIVE grows more and more in the direction that also real world scenarios can be modeled. Its maturity saves companies a lot of efforts of trying to solve this issue on their own, they just have to implement the data format import (or export) and can transform it to their own needs (e.g. only visualizing or only using specific parts of the road description). There are already a lot of data providers out there who are able to provide proper OpenDRIVE data. The fact that OpenDRIVE delivers many answers to the question of how to describe the road led Baidu to use it as basis for their HD map module in the Apollo driving stack. Why re-inventing the wheel?

By the way: OpenDRIVE is now managed by ASAM and will stay open.

Along the way, other road description formats emerged with the ambition to play an important role in the HD map buzzword war. While they are upgraded to also be able to describe the road on lane level, they are becoming increasingly complex because their format extensions have grown historically and were not designed from scratch. They continue in modeling the world based on nodes and edges.

The drawback is that it is quite complicated to derive the data stored in such maps from reality with small effort. Most of the road description formats are describing lanes but a lane is a mental model developed by humans. The traffic area often is just a plain area and sometimes infrastructure such as road markings helps us to identify lanes. But if you look into cadastral data, aerial images and construction guidelines, you see that there are edges next to the lanes and additional space between edges and pedestrian walks or bicycle ways that have to be described, too. And sometimes these areas are not following the road axis. It would be closer to reality to focus more on areal description than continuing to follow linear approaches. The Area Concept of OpenDRIVE is doing this as well as the Transportation module of CityGML in its current version 3.0.

But instead of accepting the challenge that the description of complex roads will need sophisticated description formats, some people start to re-invent and come up with simplified data models such as Lanelet2 (yes, already second generation), arguing that they did not choose OpenDRIVE because of the lack of freely available libraries. So, why not developing these missing libraries for an open format instead of creating yet another data format for which I need libraries as well? Whatever, let’s see how they will manage complex scenarios that other formats already have tackled with…

Speaking of more and more formats: There are also activities which try to simplify the complex task of precise road surveying and data transformation into various specialized formats. One of these are the Road2Simulation Guidelines which have been prepared for a standardized surveying of road and surface data. The guidelines follow the road description format OpenDRIVE and the surface description format OpenCRG, but require much less syntactical knowledge of these description formats. In Road2Simulation a simplified data model based on OGC 3D Simple Features is used to transform road elements into specific formats, not only into OpenDRIVE.

Coming back to the automotive domain. There are a lot of tools out there still thinking that you can force OEM or Tier-1 suppliers to trap into a vendor lock-in. For singular use cases this might work but if you continue more in the direction of developing integrated systems such as automated driving you have the need to think bigger. Such systems not only have to be tested and homologated but also the impact of these systems has to be assessed. In the first place: Is it even profitable, for example, to deploy a mobility as a service product in a specific city? To answer that, a system’s limiting capabilities have to be taken into account. On top of that it is worth to check which impact these systems will have in the overall traffic in the second place (e.g. regarding their defensive way of driving). You will need models of the automated driving system to simulate its behavior in traffic flow simulations. But the most important use case will still be the validation and verification of the safety of the intended function (SOTIF) and that requires testing of a huge number of situations in numerous variations. For that, many different tools such as sensor simulation, the self-driving system, traffic and environment simulation have to interact with each other based on the same data to generate trustworthy results!

Second Force: IT Giants

To develop automated driving there are currently two approaches: Trying to advance driver assistant systems more and more to an integrated system that allows automated driving or starting from scratch and consider this task as IT use case. The Financial Times had recently published an interesting article about both approaches. Nevertheless, what we see is the following: While OEMs are continuing to follow their overall development strategy and tooling (using simulation for development, test, validation and verification) the new IT players in the market start with the same habit as the simulation tool developers in the earlier days: Everybody is developing on their own, thinking that his solution is the best among others. But here the simulation is even more needed for generating a lot of test kilometers to find possible and new unknown scenarios and test them as well. But do you believe that the most valuable thing that these automated driving companies are developing is embedded in the road and environment description? Or is it more perception, prediction and driving strategy? Thus, why waste the time in developing your own map representation that nobody else can use and deliver? Every city where these companies want to deploy their service has to be mapped by them (thousands of kilometers) instead of only collecting training data to adapt to the local driving behavior. Will this really scale? But it seems to be the solution to develop everything on your own. Backed with billions of venture capital and, therefore, not having the need to generate profit in short-term, this might be a solution (if nobody cuts the accrual of venture capital). As you have seen: Zoox would have been vanished if Amazon had not invested some pocket money.

At least Mobileye share their lane-level road data called “Road Experience Management™” (REM) collected by a huge vehicle fleet with installed Mobileye cameras (e.g. vehicles from BMW, Audi, Volkswagen, Nissan, Honda, General Motors). This data is used by Mobileye for their own automated driving solutions as announced at the IAA Mobility in Munich lately. But this crowd-sourced data (sold from the OEM to Mobileye) is not only used by Mobileye themselves but can be again re-licensed by the OEM… and if the OEM add extra money, they not only get the data derived from their own vehicles but from vehicles of the other manufactures, too! This is, at least, some kind of data sharing and we never argued against putting a business model on top of the digital twin.

But wait. Did I mention public authorities at the beginning of this feature? Yes, we also have to talk about them before we can come up with an overall conclusion.

The Battleground and the City

Cities remain cities. They built new roads and housing and developed new commercial areas but they did this in the usual and traditional way. Slowly, IT support was introduced and data digitalized. Often, tools from different providers were purchased – and, guess what – which provided a proprietary implementation. If you want to have the same kind of data from different cities, you will get it in different formats. Even now, Open Data portals of different cities have different (user) interfaces and provide different scales of data. One positiv example is the Urban Data Platform of the city of Hamburg not only showing data but also making it available using web services. With the help of standardized interfaces, third-party application can reuse the data provided by Hamburg, too.

This works quite well for point-based data and networks but often cadastral plans representing the road area and its infrastructure were only digitalized in a visual way, neither semantic meta-data about the edges were added nor were roads connected to other roads or areas were topologically closed. You can call this “digital paper” which is basically worth nothing when viewed from a programmatic data processing perspective. If you want to process this data, you have to apply computer graphic algorithms and possibly a whole bucket of AI first. With the next “digital sheet” from a different provider you start re-training from scratch.

Also, the urban development process itself didn’t really change and additionally the requirements didn’t change either: Most of the space is still reserved for individual motorized traffic, intermodal traffic and sojourn quality are unknown terms. Slowly, the understanding grew that there will be some mobility trends which have to be incorporated: Electric mobility, for example, needs an improved energy supply not only for car parks but for entire neighborhoods. And some mobility trends struck cites like by a lightning: From one day to the next huge fleets of rental bikes (and later rental e-scooters) flooded big cities and residents began to complain about them lying around everywhere. Public authorities did not really have a solution how to manage “biblical plagues” but some started developing solutions.

As we already stated in our stakeholder feature there are currently a lot of parties interested in using the traffic area. Cities have to realize that this traffic area and data about it is the key to a lot of mobility solutions and to answers of how to manage them. As ambassador of the citizen they have to take the task of steering the new mobility trends instead of just reacting to them (slowly). Cities have to apply rules and enforce them to maintain working and useful traffic structure.

One solution was developed by the Open Mobility Foundation (led by the City of Los Angeles) and is called Mobility Data Specification. MDS implements an API for cities and private companies to securely interchange data with each other. Mobility providers are enabled to report information about location and status of their vehicles as well as their ride history. Public authorities can dynamically apply policies to manage either the overall traffic or specific vehicles. Agencies can connect cities to solve transport issues on a “global” level.

Especially the deployment of policies helps to fight man-made plagues: Mobility providers have to react on cities’ rules or they are not allowed to continue their service. The rules can define that trips with e-scooters cannot be finalized in specific areas because it is not allowed to park them there. And what helped to bridle the vast amount of e-scooters can be used for upcoming ride sharing services as well, can’t it? Or apply regional policies to reduce noise while switching from combustion mode to electric as Scania is providing this for their fleet customers called Scania Zone.

Not only that the mobility providers might have to share their trip data they could also share sensor data about the environment and infrastructure. It could be a service in return for community to support finding damages of the road or supply infrastructure or monitor traffic congestion for being able to use the public roads. This information could be used to build a common map data ground truth that is provided to everybody who wants to do business on the roads. Thus, they can focus on developing and improving their services instead of surveying the city again and again, again and again without sharing the data. Additionally, the taxpayer has not to fund such kind of activities done by the public authorities any more and the money can be spent on more specialized surveying topics such as aerial images etc.

Steering mobility is one important part but even more important is the long-term planning, which has to consider new trends in mobility. We already wrote that if it comes to urban planning, citizens want to be involved in the decision making process. Therefore, it is necessary, for example, to generate visualizations of variants of a project and to create simulations of the variants’ impact on traffic, noise, shadowing, airflow etc. All these data should be presented and made available to the target group – if possible as open data so that everybody can work with them and verify the results. In that way decision-making is heavily supported and acceptance is guaranteed.

One solution is having a digital twin of the city with all relevant data about roads, infrastructure, energy flow etc. linked to each other. It won’t be one big database but a federation of them using different specialized data formats for describing expert information. Therefore, the linkage of the data using standardized interfaces is absolute crucial to not getting lost in data. But re-inventing the wheel by creating your own proprietary data format does not contribute to the overall mobility challenges society has to face. Contribute to improve open standards that others can use is way more useful for mankind.

Conclusion

The format war is just the tip of the iceberg… it’s more like the Wild West and we are right in the middle of gold rush era. Everybody is doing their own stuff, believing that they will find a (or the) gold mine. New proprietary formats are developed without being compatible. Everybody has to map the same world, thus synergies are required (did somebody mentioned updating of map data?). Cleaning, processing and fusing of the data also has to be done by the parties themselves. If mapping companies come into play, they have to understand each new format and implement it accurately to deliver reliable data. The OEMs learned from their history and more or less are collaborating in standardizing formats and tools. The new IT players start from scratch, because they start from the IT side of the problem (solving the problem of automated driving with algorithms and data) and not taking the OEM side into account (being able to prove safety from start to finish) in the first place.

Meanwhile, public authorities have to start acting as stewards in digitalizing mobility, the corresponding services and especially the playground. They should start to build digital twins of their cities and to persuade interested stakeholders to contribute to this data management. There should be benefits for everybody to get fresh maps and up to date traffic data because everybody is contributing their data. Public authorities should not be the proxy of the IT giants because cities have to take care about their inhabits and the public infrastructures. IT or OEM companies take only care about their shareholders…