Experts’ voices: The GIS year in review

December 31st, 2025 | by GEONATIVES

(9 min read)

We could hardly have wished for a better end to our 2025 series of posts than by (virtually) sitting together with Michael Scholz, research associate and spatial data cruncher at the German Aerospace Center (DLR e.V.) in Braunschweig. Read here what we found out about 2025 in review when it comes to geodata.

Not only with his daily work but also with his activities in FOSSGIS and visits to FOSS4G events, Michael has a great overview of trends and topics in the GIS domain. An almost “classic” topic is the publication of datasets by different stakeholders and the trend to make open data available to the broader public. Unfortunately, these efforts often still tend to be driven by federal states and even cities themselves without alignment across borders, thus rendering many of the portals’ data incompatible with each other. Though, basemap.de can be seen as a prominent example for successful alignment of cross-federal activities in Germany into one consolidated web map database.

Additionally, some communities just focus on their daily business with case studies and product roadshows. The focus is still on cadastral data, with just little high-definition map or road-space point cloud data. Occasionally, earth observation data is processed. Looking outside the box to utilize the existing data for mobility and logistics applications or to incorporate requirements from this remote sensing domain does not take place. The topics of different domains such as civil engineering, automotive, railway, urban planning etc., are still handled isolated with only little interchange between the communities. Also, the communities’ conferences often don’t feature many outside-the-box presentations and tracks. The UITP Summit this year in Hamburg is a good example how public authorities, research and industry from the domain of mobility and transport can meet. Fortunately, there are some public frontrunners (as well as private big tech players) active and more and more suppliers with fresh and cross-domain ideas are emerging to provide their services.

Urban digital twins

Among the silos there are some highlights which may set new trends and influence the community as a whole. The “Connected Urban Twins (CUT) project of the cities of Hamburg, Leipzig and Munich aims to advance the development of data-driven urban twins (Digital Twins) [..]. Through the cooperation of the three cities under the leadership of Hamburg, common standards are to be developed for this purpose that can also be replicated and applied across metropolitan regions and other cities on an international scale.” (source: website).

Outcomes of this effort are the Urban Model Platform (UMP) and the Urban Data Platform (UDP). The so-called Masterportal to these platforms is developed in agile method with frequent meetings. Even though each city can maintain its own fork of the software, they all refer to a common basis, thus minimizing compatibility issues and enabling re-use of services. Focus is on open platforms as well as open data.

But, why are they doing it? Because it’s a business case for cities to provide and operate the (public) data and for suppliers to provide services and maintenance. But fortunately, there is more drive than just this business case; the consortia of larger cities understood the advantages of having such kind of “ecosystem”. A common database of models and data may be used for simulation, for example, of sound propagation, photovoltaic potential or airflow analysis in urban environments. Where the (simulation) model is universally usable, only the data of buildings etc. needs to be exchanged to compute the results for different regions of interest. This saves considerable effort and money. A big advantage of the current solution is also that unified OGC interfaces may be used to link different data sources. Overall, not only data, but also processes, scenario descriptions, parameter settings etc. may be exchanged between different users by utilizing standards such as OGC API – Processes. An API can get extended to let flexible web frontends consume parameters to run computing services in the backend and instantly show the specific results to the user. This idea could be extended to integrate a microscopic traffic simulation taking even more data into account but nevertheless building upon generally accepted data formats and simulation models.

As Michael describes, he has seen many other projects working with a very low level of data and model reuse which requires all of them to “reinvent the wheel” in order to reach a stage that they could also have reached off-the-shelf to a large extent if they had dared to get in touch with a “neighboring engineering community”. Very often, data processing methodologies are generic and thus applicable across domains to various application use cases – especially regarding spatial data processing. It’s not like in research projects where basic questions may need to be addressed, and research is sometimes done for research’s sake.

Outcomes of research projects could be more useful if they provided data and processing methodology (making new computing models available via standardized processing APIs) in a similar open way to get it integrated in different platforms more easily. It would also be beneficial if research contributed in a more fundamental way to standardization and committee work instead of having the need to “wrap” the standardization work in temporal, time-limited research project work packages. Additionally, (public) research projects should address license issues more consciously to make the results also available for industrial use. Currently, the focus is more on technology transfer (reads: licensing) instead of making the result of projects funded by taxpayers’ money available for everybody. Often, specific technical data formats don’t have the necessity to be developed because the problem is missing data, not missing features.

Available standards are often already mature enough to cover various edge cases but the implementation of these standards in software lacks behind. Outdated tooling and missing understanding of the capabilities of data formats and what the software is interpreting leads to discussion that a new dataset has to be created instead of working with existing data and rather fixing shortcomings in available software. It is the starting point of the reinvention of the wheel and happens in research as well as in industry (called “not invented here” phenomenon). In contrast, municipalities have the clear task of solving very specific problems and making sure that results from their work can be processed further downstream.

Looking beyond Europe

Beyond Europe, the landscape looks less structured. There are, however, services for geodata, maps and the like, and it seems that small companies are increasingly offering them. They tend to use open-source solutions and to extend them along with their needs.

Asked about further research activities in the area of geodata, Michael states that he’s too little involved to provide a comprehensive overview but that he sees interesting communities in the areas of remote sensing and earth observation. One trend that he emphasizes is the transfer of processing tasks onto the satellites themselves (similar to the edge computing in vehicle-to-infrastructure communication), thus reducing the need for transferring raw data (and the respective bandwidth).

Another community – which has less geofence – that definitely has to be on each geodata enthusiast’s radar, is the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC). Its member meetings are great places for talking about data standards, interoperability specifications for processing and data transfer and the like. At the member meetings, remote sensing, transportation and civil engineering domains come together and start working cross-domain. Sometimes, re-inventing is back on the agenda, e.g., if there is the need for developing a new high-definition (road) map format. This is where the hard work begins: bridging gaps between domains to form a common understanding and to find a common solution.

A geodata user’s year in review

We asked Michael about his experience as a user of geodata in the past 12 months. He pointed to a challenge he had with trying to correct a datum in OpenStreetMap (OSM). After he noticed that a mountain’s summit was in a slightly wrong place on the map, he tried to correct it. But, (un)fortunately, the data (location and height) was linked to Wikipedia and Wikidata, and it was unclear how the best practice for changing it directly in OSM looked like. After investigating for a while he seemed to have ended up in an infinite loop of mutual references of different open data sources, but the used licenses wouldn’t allow for direct imports of one data source into the other or vice versa. He figured out that there didn’t seem to be a single source of truth for the datum of interest in this case. How to keep the system consistent if one of the systems gets updated? Why is it not in sync at all? We discussed whether licensing or data governance might result in issues preventing data changed in one place to be reflected in a linked document but didn’t come to a final conclusion, unfortunately.

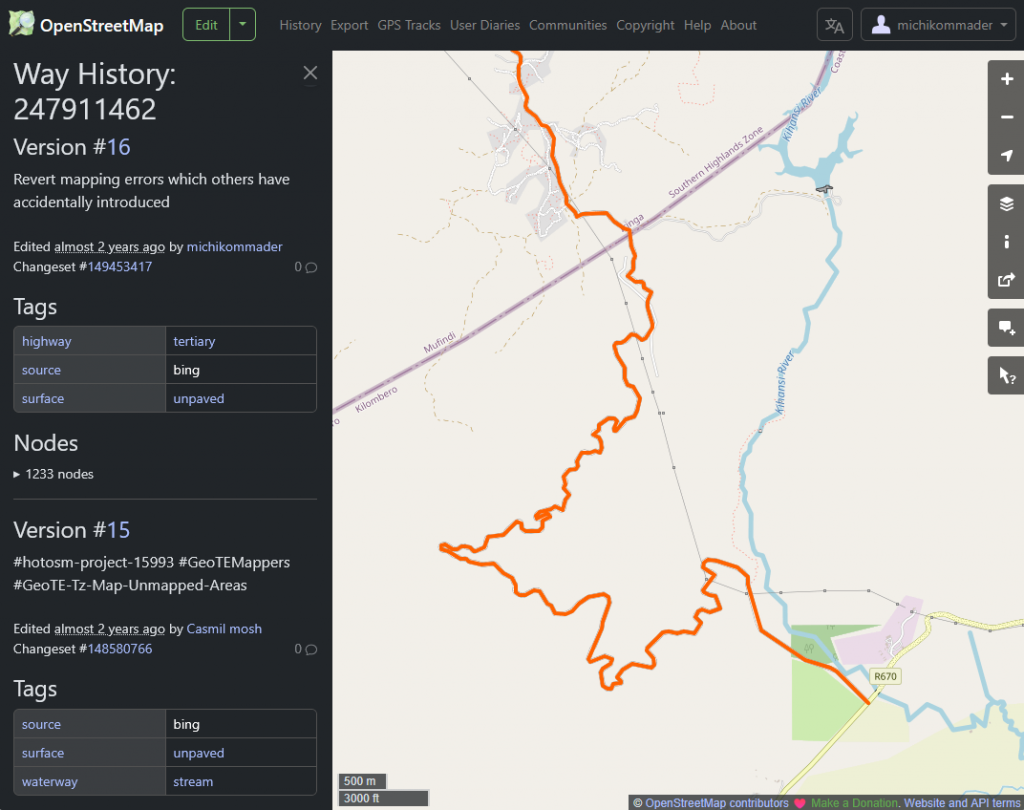

This led to a discussion about another aspect of crowd-sourced data: who is right and who has the final word? Michael is frequently traveling sparsely or incompletely charted terrain in East Africa. After having mapped a few streets in one region, he noticed the next time he looked at the data that someone had changed their type to “river” so that they were no longer usable by vehicles in routing applications. When correcting the data and reassigning the “street” attribute, he also had to convert each river crossing (ford) back into a street crossing manually. Now, he’s dearly hoping that nobody will change the attributes back again to their wrong values. The change happened by a humanitarian OSM project that orchestrates campaigns to update maps of special locations. But there is apparently no or incomplete review of the changes taking place. The editing software varies and does not necessarily provide plausibility checks, and no automated change detection seems to be conducted. Algorithms in GIS applications are often fine-tuned to specific data but not generalized to enable plausibility checks. Thus, changes have to be reverted manually if noticed.

But who has the say? Who “owns” the correctness of map data? There are communities like FOSSGIS who take care of the OSM project. Nevertheless, each user has the right to change data – for good or bad. And each user has the right to come up with their own “modeling style” when it comes to using the different elements of OSM. Another example by Michael has been the definition of a national park’s border that coincided with the definition of a forest. At some point in OSM, two separate polygons are used to describe the differently attributed properties whereas at other locations, a single polygon with two attributes is used. Now, what’s the right way to do it?

The truth in geodata

In the current times of conflicts and disputed borders, it might be very hard to say what’s the true geodata. But we can also work on a larger scale and try to remove bias in the depiction of geodata. One such project is the Equal Earth Project which provides maps depicting countries and continents in correct relative sizes. And it also provides different options where the meridian may be placed for a world map rendering. For all of us who are traveling the world and attend conferences here and there, it might be a common experience to see world maps centered around different regions. But isn’t it just an expression of the feeling that everyone sees the world rotating around themselves? Anyway, the Equal Earth Project provides you with an option to see you or someone else as the center of the world.

Wrapping up the year

We ended our talk with Michael, asking about his single positive and negative geodata highlights in 2025. On the positive side, there was a project deriving infrastructure (i.e., 2.75 billions of LoD1 buildings existing in 2019 which is more than the previous existing databases covering 1.7 billion buildings but missing most of Africa and South America) information from remote sensing data, a project already referenced in a paper from 2021, and on the negative side, it is – again – the tendency of players in the (research) market to reinvent the wheel. We can only emphasize what Michael is repeatedly asking people for: look at what’s already there before you reinvent everything just to make something work that would be feasible as a small extension to existing solutions.

Next year will be another challenge, but Michael expects geodata processing to benefit a lot from support by AI tools in data acquisition and processing (e.g., data extraction support from satellite imagery) fed by trainings data based on direct user action. Hopefully, these AI helpers driven by big tech players in geodata domain will finally know which wheels have already been invented and will make best use of them.

Thanks

A big thanks to our GEONATIVES colleague Michael for finally agreeing to being interviewed by us and for providing information from behind the curtain to our readers 😉.